CRISPR focused project looks to halt methane emissions at their source

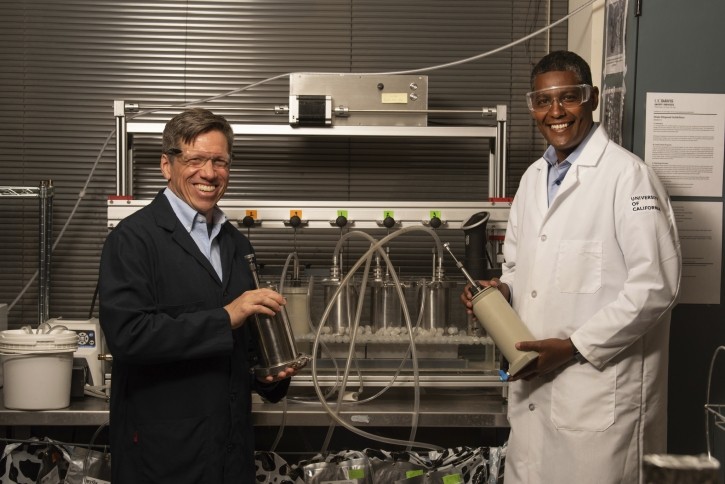

UC Davis professor, Ermias Kebreab, who is known for his innovative research on seaweed feed supplementation to reduce methane emissions, and associate professor, Matthias Hess, will collaborate with a world-renowned team at UC Berkeley: Professors Jennifer Doudna and Jill Banfield, as per a release from the university.

Doudna won the 2020 Nobel Prize in chemistry for her work to develop CRISPR genome-editing technology. Earlier this year, Banfield became the first woman to win the van Leeuwenhoek Medal for her impact on the field of microbiology.

The initiative will be funded by TED’s Audacious Project, its largest financing effort to date.

Kebreab, an animal scientist and associate dean of global engagement at the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, and Hess, a microbiologist, will serve as co-principal investigators at UC Davis to build on their successful work reducing methane emissions in livestock.

Doudna and Banfield will lead the initiative at the Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI) at UC Berkeley. They are applying CRISPR genome editing and genome-resolved metagenomics to microbiomes.

Engineering microbes

Methane emitted in cow burps comes from gas-producing microbes in the gut. Engineering these microbes to produce less methane would help limit emissions before they are burped out, said the researchers.

“We’re trying to come up with a solution to reduce methane that is easily accessible and inexpensive, without restrictions or limitations, and that can be made available not only to California but globally,” said Hess.

Hess and Kebreab want to be able to deliver oral treatments to calves to intervene in their microbial systems at an early stage and reduce methane emissions for the rest of their lifetimes. While this is hypothetical for now, early studies offer hope it could eventually become a global practice.

“Engineering microbes directly where they live, without the need to isolate them, has not been done yet because there is no tool to do it. Now, with UC Berkeley, we will be developing those tools,” said Kebreab.

Lab and field tests

Hess and Kebreab’s labs are pairing up their complementary expertise: Hess will evaluate the microbial tools and biocontainment strategies developed at the IGI in a lab setting, then he will deliver findings and results to Kebreab to apply to the animals out in the field.

California has a mandate to reduce methane emissions 40% by 2030. Because methane does not stay in the atmosphere as long as other gases like carbon dioxide, reducing emissions now will have a visible impact on the climate within the next decade, said the scientists.