Methane busting strategies: NZ farmers to pay for their emissions?

New Zealand is currently the only country considering a compulsory emissions price on agricultural emissions, although such moves have been debated elsewhere.

The Committee’s report Action on agricultural emissions outlined various ways that a farm’s emissions could be calculated.

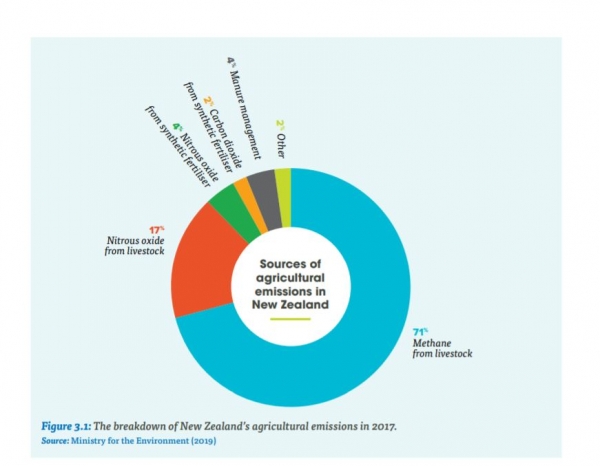

The agriculture sector is a significant contributor to New Zealand’s economy. Each year it generates 35% of export revenue. Most of the country’s meat, wool, milk and wood are exported, and some of its crops, fruit and vegetables. However, agriculture, particularly livestock farming, generates emissions of two greenhouse gases – methane and nitrous oxide. Together, they make up almost 48% of New Zealand’s reported greenhouse gas emissions, noted the report.

Emissions pricing

Tackling agricultural emissions would require a package that includes both emissions pricing and practical support to help farmers understand how to move towards lower emission land uses, concluded the Committee.

It defined a two-stage process for implementing emissions pricing for methane and nitrous oxide emissions from livestock:

- as a first interim step, price these emissions at processor level through the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), and

- as a second step, by 2025 implement a farm-level emissions price via a levy/rebate scheme that is integrated with the ETS.

“Pricing agricultural emissions would encourage farmers to factor emissions into their everyday decision-making. The money from pricing emissions would be recycled back into programs that help farmers reduce emissions," said the authors.

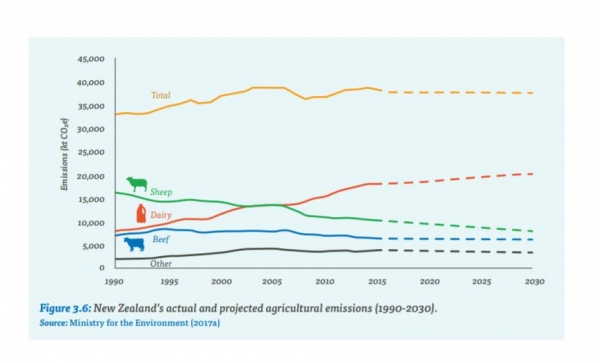

Innovation in the NZ agricultural sector has reduced its emissions intensity (emissions per unit product) by about 20% over the last 25 years, reported the Committee.

“But overall agricultural emissions have increased 13.5% since 1990. The improvements farmers have made have helped keep agricultural emissions relatively stable since 2012.”

The Committee said the less methane emitted in the future, the less New Zealand will contribute to global warming: “But methane is a relatively short-lived gas, which means it does not necessarily have to be reduced to zero. Consequently, there is a debate about what the long-term reduction target for methane should be.”

Farmers' reaction

The Action on agricultural emissions discussion paper is a positive first step as farmers and the government hammer out a practical path to reduce livestock greenhouse gas emissions, said NZ farming representatives, Federated Farmers.

“We are agreed that a priority is to find a workable and affordable way that farmers can measure emissions and sinks at the farm level, and to adopt practices and any new technologies that will help drive down methane and nitrous oxide emissions,” said the farming group's climate change spokesman, Andrew Hoggard.

“Where we differ is that the government keeps emphasising pricing as the predominant tool. Federated Farmers does not agree with universal pricing of methane. The ETS has failed to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from transport – in fact, transport emissions have near doubled since 1990. Universal pricing of methane will be similarly unsuccessful."

Federated Farmers said it has committed to working with the NZ government to design a pricing mechanism where any price is part of a broader framework to support on-farm practice change. Such pricing would be set at the margin - that is, only applying to methane emissions over the 0.3% yearly reductions that scientists indicate is enough to ensure methane no longer adds to global warming, added the organization.

The farming representatives warn that if New Zealand’s milk and meat export volumes reduce as a result of lower on-farm production, the gap will be filled by less efficient producers. "This is known as “emissions leakage” and will ultimately increase global emissions and food costs. So any pricing should only be a tool to incentivise farmers into taking up economically viable opportunities to cut methane."

Short-term methane emissions curbing actions

The Committee, in a Q&A summary, provided a few examples of what actions farmers could consider now, including:

- Maintaining production by increasing animal performance while reducing stocking rates

- Shifting to a less intensive system

- Improving the efficiency of fertilizer use

- Using different feeds

- Diversifying farm operations

Longer-term reduction strategies

The report also documents how, as research progresses, new methods for reducing on-farm emissions are likely to become available including the use of low-emissions animals, nitrification and urease inhibitors, methane inhibitors and a methane vaccine.

Livestock can be bred to emit less methane for each kilogram of feed they eat; in the same way, they can be bred to produce more milk or meat, according to the authors.

“Sheep that emit less methane have been identified and scientists are looking at how this low methane trait can be added into the sheep breeding index. It will take several generations for this genetic trait to filter through the sheep population, but it has the potential to reduce emissions by about 5%. Low methane sheep are currently being tested in a large-scale trial across the country.”

Selective breeding for low methane cattle is further off. It is harder and more expensive to identify low emitting animals, they said. Genetic markers, microbial markers and markers in milk are all being assessed for their suitability for use in breeding programs.

Methane inhibition

More promising, perhaps, is methane inhibition.

A methane inhibitor is a chemical compound that inhibits methanogens – the microorganisms in the animal’s rumen that produce methane. To work effectively, the inhibitor needs to influence the activity of the methane-producing microbes. This makes effective mitigation challenging in grazing systems. It is easier to achieve mitigation in confined systems, said the authors.

The report references the fact that a methane inhibitor, 3-nitrooxypropanol or 3NOP, has been developed in Europe by DSM to work in these more confined livestock systems.

"Published trials suggest that 3NOP could reduce methane by a minimum of 30% if it is present in every mouthful of feed that an animal consumes. In New Zealand’s grazing dairy systems, it has been estimated that if fed to animals twice a day when they are milked, it could potentially reduce methane emissions by about 5%.”

Research is underway to develop slow release inhibitors that could be used more effectively in New Zealand’s pasture-based farming systems, added the authors.

Vaccination

The committee also wrote about the promise offered by methane vaccines, how they could be used to trigger an animal’s immune system to produce antibodies that suppress the activity of methanogens in the rumen.

“Research to develop a methane vaccine is in the early stages. Some success has been achieved in laboratory studies but it has not, so far, been proven to work in animals.

“This makes it difficult to say when it will become available.”

Scientists, they added, estimate that a methane vaccine could result in reductions in emissions from individual animals similar in magnitude to those of a methane inhibitor.

“Such a vaccine is likely to be suitable for use in most systems of production both nationally and globally.”

Genetically modified ryegrass

Genetically modified ryegrass has been developed by scientists at AgResearch and is currently being tested in field trials in the US, said the committee.

“Initial modelling suggests that using this grass could reduce both methane and nitrous oxide emissions from grazing animals, but there are no results yet from actual farm trials to confirm its efficacy.”

They noted that current laws relating to genetically modified organisms would prevent use of this in New Zealand.

There are feeds that can, in some circumstances, reduce methane or nitrous oxide emissions from livestock, said the authors.

“Examples include forage rape, maize silage and fodder beet. The size of any reduction is highly farm specific.”